Name: Ania Trzebiatowska

Career Background: Festival Director (Sands: International Film Festival in St Andrews), Feature Film Programmer (Sundance Film Festival), Artistic Director (Off Camera IFF in Krakow, Poland), Film Sales & Acquisitions (Autlook Films, Visit Films), Production & Post-Production (BBC), British Museum

With her career background in international film festival curation for Sundance and Off Camera, Ania Trzebiatowska is now bringing her experience to Fife, directing the inaugural year of the new Sands International Film Festival in St Andrews.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your background.

I’m the Festival Director of Sands International Film Festival in St Andrews, and I’m also a film programmer for the Sundance Film Festival. That’s sort of my “main job” – a full-time position with Sundance. I’m based in Los Angeles most of the year. I’m now lucky enough to be in Scotland to get ready for Sands.

I’m been programming / curating films for most of my professional career. I trained in production and in post-production, but I kind of stumbled upon curation, and that’s always my favourite thing to do.

I used to run a film festival back home in Krakow in Poland called Off Camera. It’s a film festival that’s dedicated to independent film, and we specialised in first- and second-time filmmakers, which is not dissimilar to what we’re doing with Sands: trying to support new voices and beginners in the film industry, and trying to create that space for filmmakers at the beginning of their careers.

Curation and film programming has always been a passion of mine, and I really just like figuring out what might work in a specific community: in terms of what people might want to see, how to maybe push the boundaries of what they think they want to see, and sort of bring voices that I think they might appreciate. So that’s what we’re doing with Sands.

Where did your interest in film come from?

Back in high school, when I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my life, I was supposed to go to law school. I think it was just something that people were doing. I was always interested in film, and it was one of those hobbies that you just have. I read a lot, and I used to watch a lot, and I was interested in film criticism but I didn’t quite think that it could be an actual profession that I could go into. It didn’t seem serious enough.

So, I was going to go to law school like most of my friends at that time, but then I watched Wim Wender ‘s Wings of Desire in one of the film clubs I was a part of. It just blew my mind. I couldn’t believe a film could do this in terms of just the poetry of it; the way that it’s put together, and how it’s basically poetry on screen. I felt like I couldn’t understand half of it, and I wanted to re-watch it to “get it”. So then I thought, why don’t I do something in terms of learning how to understand films like this?

I decided to apply to the Film Studies department at Jagiellonian University in Krakow. It was an insanely competitive year, and luckily my parents were not very pushy about me deciding what I wanted to do. They just let me go with it. I think they tried to steer me in that direction of maybe having a Plan B, but I told them that I didn’t really see myself studying anything else, and if I didn’t get in I would just study something else, or maybe go abroad and work, or whatever else, but I applied and I got in.

It was kind of like a dream come true for a while, because it really meant I could just watch films and write about them. For a while I really was convinced I could go in the direction of film criticism and try to make money off of that, but I just didn’t really like the environment of it. I didn’t like the fact that a lot of film critics that I read ended up writing about themselves more than about the film. It’s actually really difficult to write a positive review of something, in my experience. People enjoy writing bad reviews of things. It feels easier, and I think to actually really be in awe of something is quite complicated, and to do that in an eloquent way too. It just didn’t feel right for me; it didn’t feel like the right profession to be in. So, I started just looking more in the general industry and figuring out what I wanted to do.

I tried editing, which was a lot of fun, and it was a very good lesson for me just in terms of how stories come together. I thought it was great, but personality wise it didn’t quite match what I liked to do. Sitting around for hours and hours. I tried production as well, and then an opportunity presented itself for me to program for Off Camera. They needed a scout to go to Edinburgh, and because I was based in London at the time it was very easy, and they sent me to watch as much as I could and suggest films that I felt might work for Krakow.

And that’s how it all started. That’s how I discovered that this could be a real job and you could really curate films. And everything I’ve done since then, even if I tried other things – I’ve produced films, I did other things within the industry – curation was always thing that gave me the most satisfaction and just feels like something I’m most suited for. So, when I got the opportunity to program Sands, it just felt like such a fantastic thing for me to do in a different country.

Why is there a need for an international film festival in St Andrews?

Maybe there’s something arrogant in saying that there’s a “need” for it. I think it’s more of a “want”, in our case. I wouldn’t presume anything, and this is not to say that we think anything is missing from this particular community, because I think it’s an incredibly culturally rich place with so much going on all the time.

What I did notice is that there’s a bit of a divide between the university itself and the community of St Andrews. I would love for Sands to be a really good excuse, maybe, to try and make people come together a little bit more, and for this to not serve as a university-only event. It’s supposed to be a very welcoming and a very diverse space, in terms of how we think about film, and this is not supposed to be intimidating in any way. This is not supposed to be an academic event.

Why is the event called the “Sands” festival?

Because of our location, and because of the fact that we are surrounded by beaches. This is one of the most beautiful locations for a film festival, for sure. It’s such an important aspect of trying to get people to come to a new film festival that no one’s heard about yet, and a big part of us establishing ourselves.

It just felt like something that would sound inviting and suits what we’re trying to do here. It is because of the location, and because we’re surrounded by beaches, and it’s a very nice stretch of beaches too. It’s a theme of beginnings that we have at the festival, in terms of not just the filmmakers at the beginning of their careers, but also students that are beginning their journey in becoming professionals in whatever it is they choose to do.

When people think of St Andrews and film, everyone thinks of Chariots of Fire. Was that something you were conscious of when you were considering the name?

I know it seems so obvious, but yes. That beach is an iconic beach, and everyone knows that’s where Chariots of Fire was shot, and that’s a big deal. It’s a fun fact for the film geeks.

How have the students in St Andrews been involved in developing the festival?

It was always important to me to have students involved in more than one capacity – not just being told to come to an event that is related to the university. Students were very much involved in the making of this festival, and that was always an important part of it for us. We have a group of student curators that I was working with – kind of “curators in training”, in a sense. I think it’s a really interesting thing to do for them because they can learn more about how the process works: how you put together a film festival, why it’s done this way, and also what it needs in terms of the timeline and all of that.

Also; just how to look at films from a different perspective. Yes – you incorporate your own taste and your own opinions about film, but you have to think about who you’re programming for and if this is something that will work in that particular context. It’s just really refreshing for me to have that opportunity to talk to them about films and to see what they’re excited about, and what they think about what they see. It’s just very different from working in Sundance, for example, where I’m working with programmers who have been doing this for many year. It’s very refreshing to do it this way.

In that sense, I really do think there’s a “need” for for a festival, because you connect the more theoretical to the more practical as well. You have students who are studying film, but they don’t really know much about the industry yet, and we’re bringing people from the industry to talk to them about it. Because those people are very accessible, and they’re very good at talking about their work in an interesting way, I really hope that our community who are not students – who are just people interested in culture – they will come out to see and hear those people talk. They will be curious to know what a Casting Director does, for example; just that kind of stuff that I just don’t think you would normally have access to unless you seek it out.

How does the acquisition process come about? Is it a long process, and what’s involved in curation?

It is a long process, on the one hand, and it also isn’t. It’s one of those things where your planning takes a long time, but then the actual ‘coming together’ of everything can be a very short process when you know what you want. It’s just the figuring out what it is that you want to do, and also what’s available to you.

With us, we’re not going after premieres of any kind. We just want to have a selection of really good films that work in our context. It is much easier, because we can just go after the films that are really, really good. Whether they were shown in Glasgow or in London is not an issue for us, and it can be an issue for most of the festivals out there when they require premiere status for those screenings.

It’s a combination of being connected to the right people within the industry, and knowing who’s handling each film. It’s usually a combination of sales agencies and distributors, and just filmmakers themselves. It does help that I have those connections, and sometimes it’s just a question of reaching out to the right people and getting quick answers from someone. That does make my life easier, I have to say. It was much more difficult for me at the beginning, when I was trying to curate for the screenings in Krakow and they had no idea about the festival yet.

With Sands, it helps that it’s St Andrews. It helps that it’s a university film festival. It helps that people know they’ll be well looked after here, too, and there’s a good audience that will appreciate the films. It’s a very tight selection of films as well. I think that’s also somehow exciting for people. We’ll be showing 9 films over 3 days – we’re being very picky! I think people appreciate being part of a small line-up like this because it doesn’t happen very often; most festivals will have 100+ titles, so it’s a very different event.

We invite every single filmmaker to come with the film. This year is a little bit more complicated like that, because of Covid restrictions and a lot of people still being a little more wary of travel, and I understand that. So, we’re trying to incorporate the ones who can’t make it in person to St Andrews, who will be appearing one way or another virtually, and we’ll make sure that we engage with them. That’s also been part of what we’ve been trying to do at the festival: to have that connection with audiences, and for our filmmakers to be able to talk to our audiences here as well.

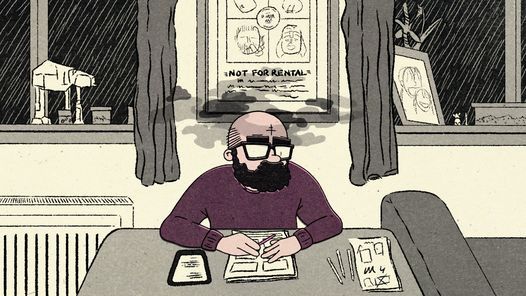

The opening night film is My Old School (directed by first time filmmaker Jono McLeod) – a Scottish documentary film previously shown at the Sundance Film Festival. Why did you think that was that the right choice for opening night?

I really wanted to open and close with Scottish films. It meant a lot to me that we would put this emphasis on local talent. Because it’s a small programme, and the ratio of 2 out of 9 films being shown being Scottish is really pretty great. Those are very impressive films, both of them.

With My Old School, there’s something about the nature of this documentary feels very original, both in terms of the story but also in terms of how it’s put together, and just how incredibly ambitious this film is. Not many people would choose that kind of project for their first film, and the fact that Jono McLeod not only did that but he also pulled it off. I just find that really impressive. I think it’s something that doesn’t happen very often. You know, we’re talking about dealing with people that are very much alive in your area, still, and just layers and layers of complexity that he managed to navigate so well.

Plus, Alan Cumming is just stunning in this film. He’s always stunning, to be fair, but in this case he’s lip-syncing interviews on camera, and you wouldn’t know. It feels like he’s just acting it out, which to me is just so impressive.

And it’s also just a very fun film. There’s so many different emotions in that film that play out. There’s a very sort-of playfulness to it in the way that it’s being told. It just feels like the perfect opening night film to me, because it gives you a sense of what the festival is trying to do, both in terms of the first time filmmaker, but also in terms of the vibe of the film and the way that it plays out. I think audiences will really appreciate it, and the fact that we have Jono McLeod there for the screening – and some of his classmates as well – and the producers… It will just make it a very special event.

The same goes for the closing night film, Long Live My Happy Head (dir. Austen McCowan and Will Hewitt), as well, because we’ll have not just the filmmakers, but also the subject of the documentary, Gordon Shaw. I think it will make for a very emotional screening and something that people won’t really forget that easily, because it is a very emotional film anyway, but when you then get a chance to talk to the people who are in the film it makes a huge difference, I think.

Do you think being able to speak to filmmakers, cast, producers, and others involved in a film can give an audience a whole new perspective?

Absolutely.

It’s always been interesting to me that – every now and then – I’d see something and it wouldn’t quite work for me. Then, I’d listen to the conversation afterwards and I’d think, “that does make sense”, and it does change the way you view something or just the way that you interpret. Or sometimes you just appreciate the ambition of something and the thought behind it. It doesn’t have to ‘work’ for you, but at least you know what someone was trying to do.

That’s another part of the whole curation process; you learn how to get over yourself a little bit sometimes: “This doesn’t work for me, but I know quite a few people for whom this will be a life-changing experience.” And those are the moments that really make it all worth it.

Sundance is a very established and prominent film festival. Setting up an inaugural year for a new film festival must come with different pressures or expectations. In what way has that been challenging or rewarding for you?

I like a bit of a challenge, that’s for sure. That’s always nice.

Whenever I feel like I already have a system in place with the work I’m currently doing, I feel like it’s good for me to push myself a little bit and to go into something that I’ve never done before.

I’ve never worked in Scotland before. I’ve worked in England but that’s a very different thing, and I have family here – my sister lives in Aberdeen – so I come here quite often anyway, and I’ve always loved Scotland so much. Maybe because I’m Polish, somehow I think the mentality is very similar, so I understand the sense of humour and it’s somewhere that doesn’t feel too foreign to me.

Also, I like studying new things. I think there’s something very exciting about the prospects and coming up with wild ideas that might not end up working out, but at least you tried and you wanted to do something new. It is challenging, but that’s the exciting part of it. That’s the part of it that makes it all worth your while. And I guess I was really excited about the prospect of working with young people – doing something that I wish I had when I was doing film studies myself, and I wish I’d had that opportunity.

How do those earlier years in Krakow feel compared to your current work in St Andrews?

Krakow is a pretty special place. Maybe I’m spoiled, because I got to run a festival in a city like that, and now I’m doing it in St Andrews. It’s so important to me to have that sense of place for me, and to feel like it’s a community where a film festival really does makes sense; where people care about culture, but they’re also curious enough to try new things and discover films.

In this case it’s a town. Krakow is not that big of a city. It’s big enough, though, and there are students there – it’s a university city – and it’s the same thing with St Andrews. It just feels like it’s a really good place to start a new event like this. There’s a feeling of “it’s not overwhelming”.

How did your own experience studying film influence your approach to engaging with students for Sands?

My favourite thing to do when I was studying was going to festivals. We’d go as a group of students to this festival called Camerimage that’s specifically for Directors of Photography. That was just a mind-blowing experience the first time that I went, because they had cinematographers who were just coming because they were excited to have their own space, and to have somewhere where they’d be celebrated.

People like David Lynch would just come to hang out because he loved cinematographers so much. I was standing there at the exhibition of Lynch’s photographs, and I couldn’t believe that this was a thing. You know, Christopher Doyle was there, and he shot some of my favourite films, and I couldn’t quite process that – the fact you were surrounded by the people from the industry who talk about what they do in such an eloquent way as well.

Creating that opportunity for other people, for students to have that opportunity to talk to some amazing people from the industry they might not meet otherwise, and in an environment that feels friendly and not intimidating… Where you feel like you can actually ask a question, and you don’t have to feel scared or that you’re not smart enough, because I also know that feeling. I think it’s nice to be in that position when it’s your own town where you study or where you live, and you can go and meet with someone amazing and listen to them talk.

The festival has also run a design competition, asking students to develop a publicity image for the festival. What motivated you to engage the students in this way?

It was just trying to find ways to incorporate as many students from as many areas as we can without making it specifically just for film students. We wanted to make sure that people understood that this is for everyone, and – again – they don’t have to be studying design or specialised in something to do with marketing to give it a shot. This was mostly about people being creative and trying to come up with something that would fit the description that we gave them in terms. We gave them a brief describing the ambition of the festival, the plan for it, and hoping for some interesting designs that they’d come up with – something that wouldn’t be too obvious.

Our head of marketing, Jan McTaggart, just said that what’s interesting is that you wouldn’t be able to commission that design, because we wouldn’t come up with that idea. It’s really just something that came from someone else, and they created it, and their reason behind it is really great. There’s something really quite attractive about what the thought process behind it was, and I just love the idea of offering that opportunity to people.

You know, whether they’re going to take it or not is a different story because everyone’s really busy right now and you don’t know if it’s going to be attractive to people, that kind of an opportunity, but it ended up working out really well, and it’s just so nice to think that this young person has their name on it, and they’ll see their work printed on things. I think it’s quite beautiful as well.

In the time you’ve been working in film curation, have you noticed any major changes in the industry? What are your thoughts on the way the industry is changing as the years go by?

First of all, in Europe we’re really lucky because we have public funding for film, and that’s not the case in the States, for example. It’s much more of an issue for people to have access to funds to do things like travel to festivals with their films. So the fact that there’s so much more awareness around funding for cultural events and filmmakers in general, and their projects, is huge – and it’s something that we don’t talk about enough, in terms of how lucky we are here to have that.

I think Screen Scotland has been doing amazing things in their support of local talent, and it’s great because it’s not just for filmmakers from Scotland but for filmmakers based in Scotland. That’s brilliant, and that also means diverse voices being given a platform that they wouldn’t normally have, and being supported at stages when they’re sometimes trying to work out what it is they’re doing.

I also see a huge shift just in terms of international relationships and co-productions. There’s so much more money being invested in that. People are really looking for ways to collaborate, which is exactly what we’re trying to do here. We’re trying to bring people from different environments and introduce our local talents to people who we bring in from other parts of the world – you know, looking to collaborate. And I think it can be a really good way to do this: create a space for people to talk and potentially collaborate later on, even if it’s not something they’re doing right now. Even if they don’t have a project that will be suitable for whoever is looking for projects right now, it might happen later on down the line, and that’s amazing if that’s the case.

In the modern world with so much entertainment competing for our attention, why is film still important?

It’s storytelling. That’s really important, and – as cheesy as it might sound – it really can change lives and change perspectives and how we look at other people as well and how we try to understand where they’re coming from.

Film does it really well, because it does combine different arts, and because it’s a visual art, it’s easier to process sometimes, and it stays with you a little bit more because these are moving images. Especially when it’s something that really is thought-provoking, and it stays with you, and it challenges you a little bit, it really has quite a lot of power to it – at least in my experience. I think it really is that inter-disciplinary aspect of it too, and the fact that it combines all kind of different art forms in a sense, and that works really well.

Obviously, there’s different ways to process films, and not everything will stay with you – and that’s probably good – but the ones that really do… There can be films that you come back to over and over. Just finding different meanings in them. Sometimes, I do feel like we maybe attach meanings to something that might not necessarily have it, but that’s kind of besides the point: it works for you, and that’s the main thing. That’s what counts.

What are your hopes for the Sands International Film Festival?

I realise that it’s not easy to have faith that something no one has heard about before will meet people’s expectations, but I guess we’re asking for that trust in our Year One, and hoping that people will come out and support us, and see as much as they can.

What’s your favourite film?

I mentioned Wings of Desire, so I’m going to stick with that. That’s an easy one – it’s my favourite film.

The Sands International Film Festival runs from Friday 25th March to Sunday 27th March at the Byre Theatre in St Andrews. For more information or to book tickets, please visit: https://sands-iff.com/